Today’s newsletter is about a psychological concept you might have heard of before: the hedonic treadmill.

The phrase “hedonic” comes from the word hedonism and refers to the pursuit of pleasure.

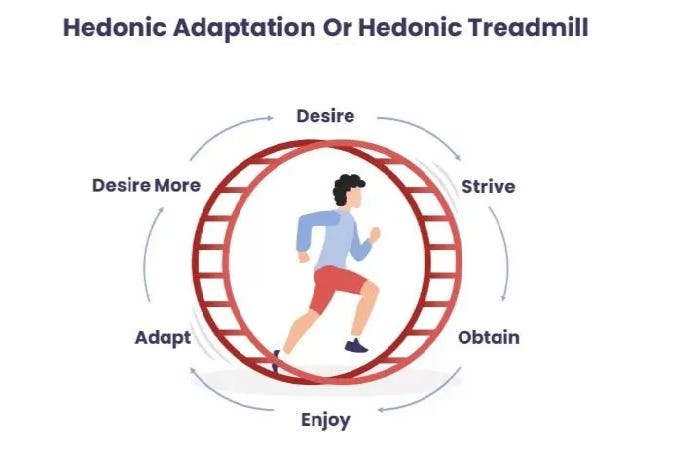

The idea behind the hedonic treadmill is simple: no matter how many nice things we have or how much pleasure we experience, humans tend to return to a relatively stable level of happiness over time.

The hedonic treadmill describes the human tendency to quickly return to a baseline level of happiness, regardless of positive or negative life events.

Imagine a person on a treadmill—no matter how fast they run, they remain in the same spot.

Similarly, the hedonic treadmill suggests that despite significant life changes, people often find themselves back at their original level of happiness over time.

This concept is rooted in the idea that humans have a relatively stable “set point” of happiness, which is influenced by genetics and personality traits.

Imagine a young man who suddenly finds fame and fortune after a video of him singing goes viral on social media.

He lived a normal life before, but now he is invited on television shows and invited to sing at events. Over six months he gets to travel the world, hang out with celebrities, and eat at the finest restaurants.

Despite experiencing all sorts of new pleasures, he may eventually get bored of the high-flying lifestyle and find that he still worries about the same things that he did before he became famous.

After the initial excitement of his new lifestyle wears off, he finds himself back to where he started.

One key factor driving this phenomenon is hedonic adaptation—the process by which individuals become accustomed to new circumstances, whether good or bad.

Even though we might be achieving our goals or getting things we’ve wanted for a long time, we find that the satisfaction of one desire leads to the creation of a new desire.

For instance, the excitement of buying a new car or moving into a new house might be intense initially, but over time, the novelty wears off, and the emotional impact diminishes.

Maybe you got a Mercedes, but now you want a Porsche. Even as we achieve our goals, we still find ourselves running in place on the treadmill.

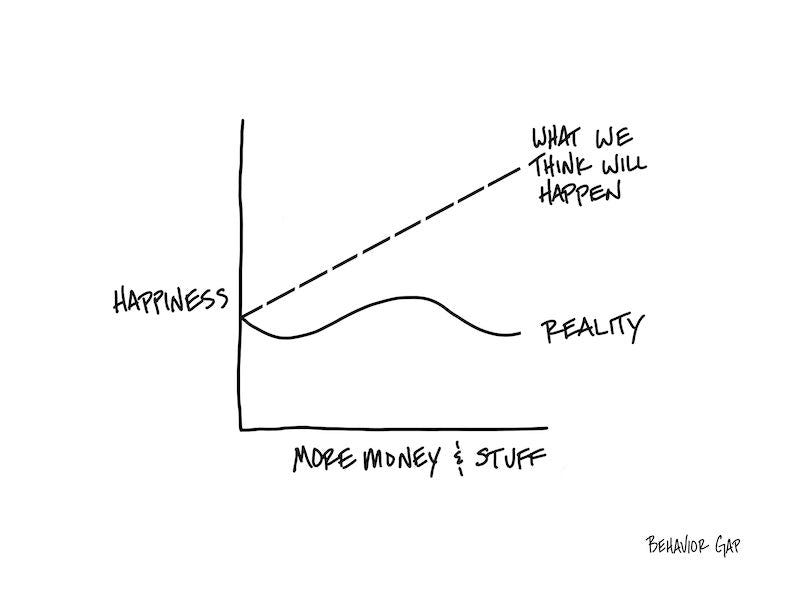

The idea of the hedonic treadmill explains why material wealth and external achievements often fail to bring lasting happiness.

Many people believe that acquiring more money, possessions, or status will lead to permanent increases in happiness.

However, because of hedonic adaptation, the joy derived from these gains is usually temporary.

This insight challenges the common pursuit of materialism as a path to happiness and suggests that focusing solely on external rewards may not lead to long-term fulfillment.

Learning about the hedonic treadmill raises an important question: how should we live?

Some, like the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus (the creator of Epicureanism), believed that life was about the pursuit of pleasure (and the minimization of pain).

The same sentiment was echoed by Voltaire, who said:

“The pursuit of pleasure must be the goal of every rational person.”

But if we just live for pleasure, we quickly find that we no longer enjoy the pleasures — and that we’re unhappy.

Historian Rick Perlstein captured the sentiment beautifully in the following quote:

“We confused the pursuit of happiness with the pursuit of pleasure.”

By incorporating the idea of the hedonic treadmill and recognizing the limits of hedonic adaptation, we can try to build our lives in a way that leads to more sustainable sources of happiness.

Research shows that investing in relationships, personal growth, and meaningful experiences tends to have a more lasting impact on well-being than material possessions.

Activities that foster connection, purpose, and personal development can create enduring happiness because they are less prone to hedonic adaptation.

Plus, the idea of the hedonic treadmill isn’t all bad. It also provides a comforting perspective on adversity.

While negative events can significantly impact happiness in the short term, understanding that people naturally adapt and recover can offer hope and resilience.

So, here are some key takeaways to conclude this newsletter with:

The things you desire won’t make you as happy as you expect

Unfortunate events hurt in the short-term, but we are resilient and will be fine in the long-term

Focus on cultivating sources of happiness that are sustainable, like relationships with friends, family, and community

Personal development (learning and mastering new skills and having meaningful experiences) will make us happier than getting new things

ART OF THE DAY

A painting depicting the unbridled pursuit of pleasure: Triumph of Bacchus, oil on canvas by Ciro Ferri, 17th century.